By Ed Kim, President and Chief Analyst

Fifteen years ago, in 2010, Nissan launched the world’s first mass-produced electric vehicle, the Leaf. Until the 2023 model year when the Ariya crossover launched, the Leaf remained Nissan’s only electric vehicle sold in the U.S. market, while Tesla and a myriad of legacy automakers and startups eagerly jumped into the EV market themselves. Worse yet, in North America Nissan was largely absent from the growing hybrid market aside from some half-baked, long-forgotten efforts that sold in minuscule volumes such as the Pathfinder Hybrid and Murano Hybrid.

Today, the EV market in the U.S. is at a crossroads in the U.S. market due to the current administration’s decision to pull popular tax credits that helped address their affordability, alongside wavering consumer interest. However, consumer adoption of hybrids has been progressively strong with automakers like Toyota, Honda, and Hyundai Motor Group aggressively implanting them in their high-volume models, increasingly as standard equipment in Toyota’s case. Today’s hybrids provide the huge consumer benefit of massively improved fuel economy with only a modest price walk, and they do not require any of the behavioral changes that are required to operate EVs, such as learning the ins and outs of EV charging or keeping tabs on range.

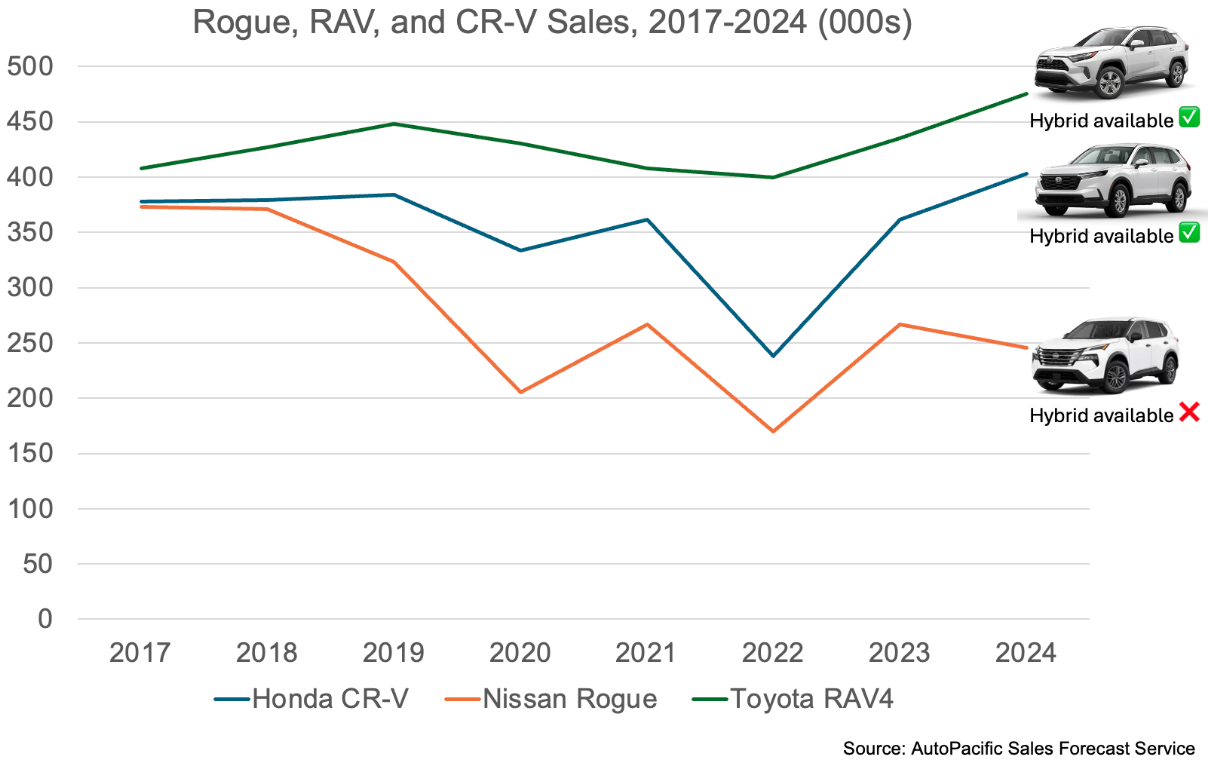

Unfortunately for Nissan and its Infiniti luxury outlet, hybrids have been missing from their current North American product portfolios at a time when the automaker’s direct competitors are attracting throngs of customers who are enticed by the massive fuel savings of hybrid powertrains. In the case of Nissan’s Rogue, its highest volume model, sales declined to about 246,000 units in 2024, down from a peak of about 373,000 units in 2017. That’s an astounding 34% drop in sales during that time period, starkly contrasted by the Toyota RAV4 and Honda CR-V, Rogue’s two biggest competitors, which grew their sales over that same time period - in a declining new vehicle market no less - by 16% and 7%, respectively, due in no small part to the availability of hybrid powertrains.

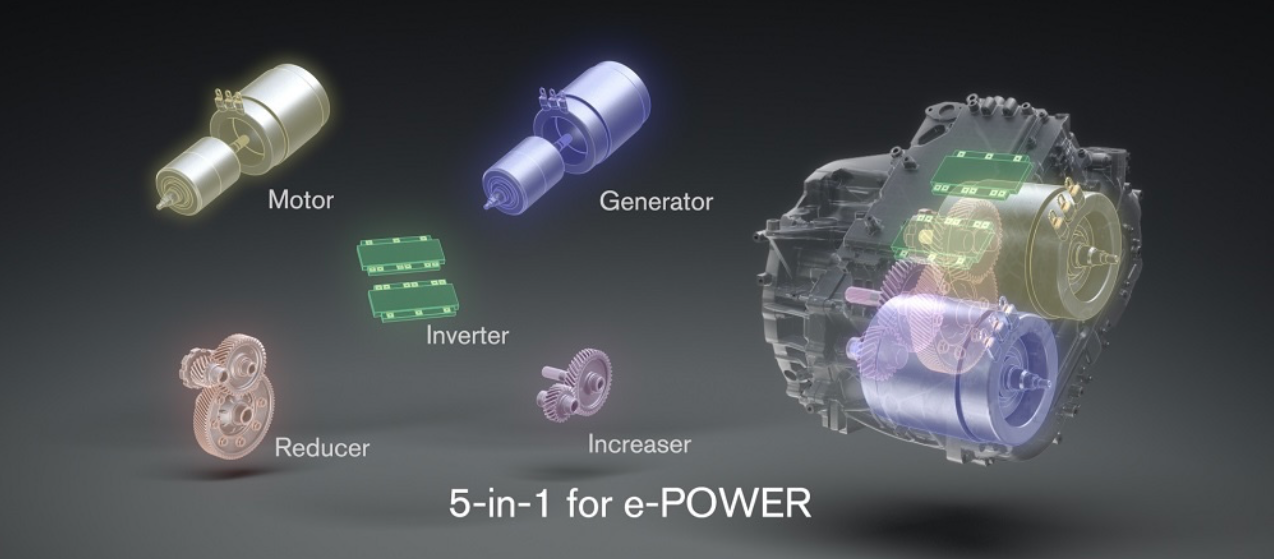

Despite its lack of North American hybrids, Nissan does have a full hybrid powertrain sold outside of North America called “e-Power”. This is a series-hybrid powertrain where the gasoline engine only functions to keep the small battery pack charged; there is no direct mechanical connection between the gasoline engine and the wheels. Rather, it’s the electric motor (powered by the battery which in turn is charged by the gasoline engine) that sends power to the wheels.

So, why isn’t e-Power offered here in the U.S. market? It’s a combination of e-Power’s technical characteristics and overestimating EV demand in the U.S. market. To the latter point, Nissan executives revealed that the original plan for the U.S. market was to bypass hybrids and go straight to EVs. However, as EV adoption was slower than expected, Nissan has ended up selling far fewer EVs up to this point than it had hoped, and it hasn’t had hybrids to sell to Americans either.

To the former point, various staff at Nissan have explained to us that e-Power in its first and second generations was designed specifically for Asia and Europe, where very low-speed city driving is the norm and drivers spend less time on long high-speed highway trips compared to Americans. This means less-than-optimal highway fuel economy in North American driving conditions.

As I spent this past summer working in the UK, Nissan graciously loaned me a Qashqai e-Power for an extended week-long test. The vast majority of my time with the Qashqai, a compact crossover about the size of a Toyota Corolla Cross or Volkswagen Taos, was on high-speed motorways (as we do in the U.S.), traversing southwest England and a bit of Wales. The Qashqai itself proved itself to be a really nice piece with a more upscale interior than we typically see in North American Nissan products (cloth-covered A-pillars, Infiniti-grade semi-aniline leather, and even massaging front seats). It was quiet at speed, plenty spacious, and swallowed all our luggage without a hitch. It was a prime example of why compact crossovers are so popular.

The second-generation e-Power hybrid powertrain, which our Qashqai had, worked well in European city environments. The speed limit in most UK cities is 30 mph, and up to those speeds, the Qashqai behaved almost like an EV as the engine tended to remain off most of the time. The EV-like one- pedal drive mode added further to the EV-like drive experience. However, cruising down motorways at 70 to 75 mpg saw the turbocharged three-cylinder gasoline generator working overtime, and I typically saw highway fuel economy in the low-to-mid 30 U.S. mpg range. Not terrible, but not particularly impressive either. A couple weeks earlier, I had rented a purely gasoline-powered Skoda Karoq, a direct competitor to the Qashqai in size and format, with a 1.0L turbocharged three-cylinder engine. The Karoq netted me highway fuel economy in the low 40 U.S. mpg range without the additional cost and complexity of a hybrid powertrain.

This experience demonstrated why the second-generation e-Power hybrid would have likely been uncompetitive in the U.S. market. However, back in March, I got to drive both the second and the latest third-generation e-Power applications on a closed test track in Japan and was very impressed with the quiet refinement of the new third generation, though the jury’s still out as to its fuel economy in American driving conditions.

Nissan’s third-generation e-Power has been thoroughly re-engineered to work well in American driving conditions, but it is still about two years away from debuting in on U.S. soil in the next- generation Rogue. Regardless, it cannot get here soon enough. Furthermore, Nissan is also developing a more traditional parallel-hybrid powertrain for its larger vehicles including Pathfinder, Murano, and Infiniti QX60. That will arrive after e-Power does.

What’s clear is Nissan needed hybrids years ago, and they can’t arrive in the U.S. soon enough. The second-generation e-Power wasn’t suited to American driving, and overestimating EV demand left Nissan flat-footed as hybrids took off. Now, with mounting financial strain and a string of canceled EV projects, the absence of hybrids is a mission-critical obstacle to recovery. Nissan must deliver competitive systems in the right segments — and quickly — to prove the wait was worth it or risk falling even further behind.